The Claim

A widely repeated belief is that eating late at night automatically causes weight gain, often phrased as "don't eat after 8 p.m." or similar time-based rules. This myth suggests that the time at which food is consumed fundamentally alters how the body processes it, making late-night eating inherently problematic for weight management.

Why This Myth Persists

The myth persists for several reasons. First, eating late often coincides with snacking, less nutritious food choices, and larger portions—factors that increase overall intake independent of timing. Second, intuition suggests the body would process and store food differently when less active (sleeping). Third, it provides a simple, actionable rule that feels like a concrete strategy for weight management.

The Role of Circadian Rhythms

Biological Timing Systems

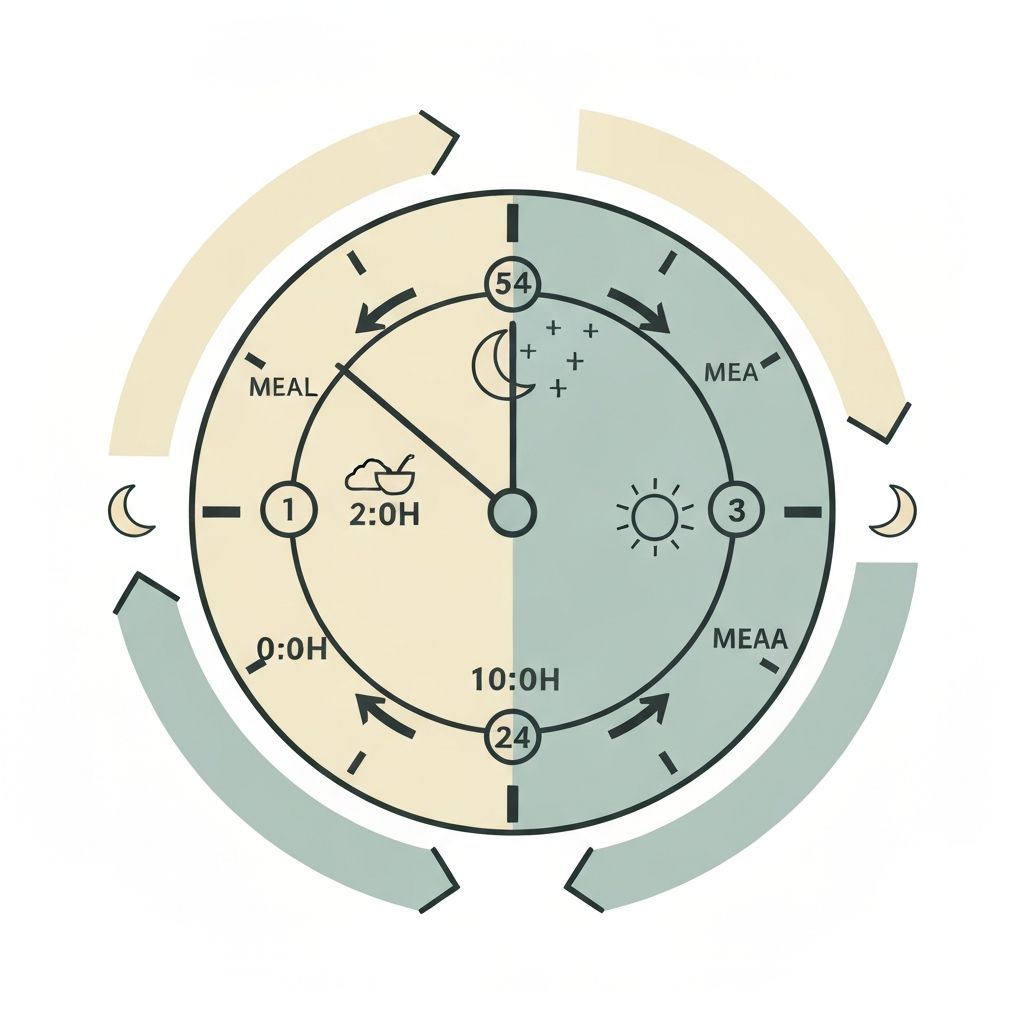

The body does operate on circadian rhythms—approximately 24-hour cycles of biological processes. These rhythms influence hormones, metabolism, body temperature, and numerous other functions. It is reasonable to hypothesise that meal timing might interact with these cycles.

Metabolic Differences Across the Day

Research does show that some metabolic processes vary across the day. For example, insulin secretion patterns differ between morning and evening meals, and thermic effect of food can vary slightly depending on time of consumption. However, these differences are modest—typically in the range of 5–15% variation in metabolic rate or thermic response.

What Research Actually Shows About Meal Timing

Controlled Studies

Controlled laboratory studies comparing identical meals consumed at different times of day show minimal differences in overall energy expenditure and weight change when total calories are equal. Studies where researchers carefully control meal composition, size, and total daily intake find that meal timing has minimal effect on weight.

Natural Variation Studies

Real-world studies examining people's natural eating patterns show that late-night eating correlates with weight gain—but this is not because of the timing itself. Rather, people who eat late often:

- Consume more total calories, particularly from less nutritious sources

- Experience reduced satiety and higher hunger in evening hours

- Eat larger portions at night than during the day

- Choose different (typically higher-energy-density) foods

When total intake is controlled statistically, the weight gain correlation with late-night eating largely disappears.

Energy Expenditure During Sleep

A common concern is that food consumed before sleep won't be "burned off" before the body rests. However, the body continues to expend energy during sleep through basal metabolic processes. Energy is not "unused" simply because the person is sleeping—it is used for maintenance of core functions, temperature regulation, and other processes. The distinction between meals consumed before sleep and meals consumed during waking hours is not as sharp as commonly believed.

What Does Matter: Total Intake and Meal Composition

Total Daily Calories

The dominant factor in weight change remains total energy intake across the day, regardless of when that intake occurs. A person consuming 2000 calories with one meal at 10 p.m. will experience similar weight outcomes to someone consuming the same 2000 calories spread across three daytime meals.

Food Choices and Satiety

Late-night eating often involves snacking rather than meals, and snack foods are typically less satiating than whole meals. This can lead to greater overall intake. Additionally, eating late may interfere with sleep quality, which in turn influences hunger hormones and food choices the following day.

Sleep and Appetite Regulation

Poor sleep is associated with increased hunger and food intake the following day. If late-night eating or a heavy late meal disrupts sleep quality, that disruption could indirectly influence weight through its effect on appetite regulation and food choices—not because of the timing of eating itself, but because of the sleep disturbance.

Individual Variation and Lifestyle Context

Meal timing preferences vary among individuals. Some people have a later eating schedule due to work or personal preference. Some experience increased hunger in evening hours. For these individuals, prohibiting late-night eating may be unnecessarily restrictive and potentially counterproductive if it leads to increased hunger and food preoccupation.

The practical issue is not the clock time but rather achieving adequate total intake, nutritious food choices, appropriate portion sizes, and eating patterns compatible with good sleep quality.

Practical Perspective

Research does suggest a few general principles:

- Eating excessively close to bedtime can disrupt sleep quality; allowing 2–3 hours between eating and sleep may support sleep.

- Evening snacking often involves higher-energy-density foods; conscious choices about evening eating can support weight management.

- For individuals prone to late-night overeating, establishing structural limits (not eating after a certain time) can be a practical strategy—not because of metabolic differences but because it prevents excess intake.

However, these are practical considerations about intake and sleep quality, not evidence that the clock time itself alters metabolism.

Key Takeaways

- Metabolic differences between morning and evening meals are modest (5–15% variation).

- When total intake and meal composition are equal, meal timing has minimal effect on weight.

- Late-night eating is associated with weight gain because people often consume more total calories and less nutritious foods at night, not because of timing itself.

- The body expends energy during sleep; food is not "unused" simply because consumed before sleep.

- Sleep quality is important for appetite regulation; avoiding large meals before bed is practical for sleep quality, not because of metabolic timing effects.

- Total daily intake matters more than when that intake occurs.

Individualised Approach

For weight management, the optimal meal pattern is one that the individual can sustain, that supports satiety, that allows good nutrition, and that is compatible with good sleep. For some people, avoiding late-night eating is helpful; for others, flexibility around meal timing may be important for adherence and satisfaction.

Educational Context

This explanation describes research on meal timing and metabolism. Individual responses to different eating schedules vary based on work patterns, sleep quality, hunger patterns, and other factors. For personalised guidance about meal timing and weight management, consultation with a qualified health professional is appropriate.